Eric McHenry

Eric McHenry lives in Lawrence, Kansas, and teaches English at Washburn University. He is the author of three books of poetry, all from Waywiser. His honors include the Kate Tufts Discovery Award, the Theodore Roethke Prize from Poetry Northwest, and a term as poet laureate of Kansas. His poems have appeared in The Threepenny Review, The New Republic, The Yale Review, and the Times Literary Supplement. He also writes regularly about music and history for The American Scholar.

Odd Evening

by Eric McHenry

Pub: Mar. 15, 2016

In his first full-length collection in ten years, Eric McHenry brings fresh attention to his old obsessions – love, laughter, justice, transience, how humility ennobles, how time makes the familiar strange and how our scars make us beautiful. McHenry can dazzle with his technical dexterity, but his poems aren’t merely performances; in Odd Evening, music creates meaning and vice versa. If books of poetry have patron saints, Buster Keaton might be this one’s: a stoic, stone-faced everyperson who’s endlessly resourceful in the face of calamity.

-

“Eric McHenry’s poems are hilarious, dark, tender, and formal. But he’s a formalist interested in the language of now and in the world we currently inhabit. And that turns his rhymes and meters into rock n roll. I love this book.” – Sherman Alexie

“To say that Eric McHenry is one of the best – and most delightful, most alive – poets of my generation isn’t enough praise. His native sense of music in English, his tonal variation, and his generosity of spirit are extraordinary. McHenry can be playful and at the same time ecstatic and practical (‘I started saying whoa whoa whoa whoa whoa. / I didn’t drop what I was holding, though’). His play is movingly traditional, yes, but also utterly modern. For this is a poet who sets today’s uncertainties and dualities to gorgeous music.” – Ilya Kaminsky

“At their brilliant outer limits, poetic form and ethical vision are indistinguishable, as Eric McHenry’s masterful poems remind us. The unforgiving injunctions of rhyme and end-stopped line refuse to euphemize, and so are particularly good at conveying the unforgiving declensions of age and envy, physical abjection, personal and institutional indifference. And, of course, poetic form this sharply rendered is also an unparalleled instrument for satire: the only bow to wickedness in these pages is wicked fun. Eric McHenry sounds like no other poet working in America today. I thank our lucky stars for his white-hot independence.” – Linda Gregerson

-

New Walk (Autumn/Winter 2016-2017)

“McHenry is the current poet laureate of Kansas and a working knowledge of Topeka can assist interpretation of some of these pieces, but inaccessible they are not. The rhythms … can be very hard to get out of your head, so you find yourself re-reading with the book closed – like it or not but you will! … McHenry is a poet to keep an eye on, and if you haven’t been doing so already, it’s well worth going back and picking up a copy of his first collection, Potscrubber Lullabies (2006), also from Waywiser, while you’re at it.” – Philip Morre

-

Canes

We should entrust them only to the old.

A cane suggests authority or sport

to anyone who doesn’t need support.

A prefect who discovers he can hold

one by the shaft, or even upside-down,

will feel the verb vibrating in the noun.A prefect is a boy. However deft

his mouth becomes at publicly explaining

the rector’s protocol for public caning,

his hand is more accustomed to the heft

and balance of a cricket bat, and trembles

to grip a cane like what it half-resembles.A prefect may impulsively suspend

your sentence after six or seven blows

when he hears titters from the first few rows,

re-grip the cane by its unhandled end,

wait for the tremor traveling through the room

to clench into attention, and resume.A lifetime of reliving this may leave

you oversatisfied with your own fitness

to judge events you did and didn’t witness

and unreceptive when you first receive

a crabbed apology for an unnamed

“sad incident of which I’m still ashamed.”Push up your reading glasses and allow

bemusement to resolve, first into rage

at the translucent, single-sided page,

the fantasy that there must be, somehow,

fraternity in your respective traumas,

his near-demotion, your blood-stiff pyjamas,then into a desire to disabuse,

then into wondering about that word,

then into bed, where you may rest assured

that any cane you dream you can refuse,

re-grip, or even raise, because your hand

is steady and you need no help to stand.You’ll wake up feeling generous and glib

and answer him at length without rereading

his letter, and you’ll leave no letter bleeding,

applying steady pressure to the nib,

producing but not pausing to admire

the measured strokes such sentences require.The Waywiser Press

Crying With Glasses On

It’s such a grownup thing to do.

Like renting tap shoes to perform

for no one in an electrical storm.

What’s wrong with you?Remove your spectacles and cry,

already. If there’s rain

on your side of the windowpane

you’re probably the sky.What’s the intention of a tear

if not to lubricate and cleanse?

I’ll tell you: a corrective lens

is making things too clear.In college I could see the future

coming and would often

pop out my contacts first, to soften

its least attractive feature.If you’ll just give it half an hour,

grief will discover

you drawing steam-roses in the shower,

and join you, like a lover.The Waywiser Press

Mommy Daddy Evan Sage

by Eric McHenry

Pub: Oct. 1, 2011

Illustrations by Nicholas Garland

“If you see a vulture, don’t play dead.”

Childhood can be a confusing time, but not to Evan and Sage. They’ve got the world pretty well figured out, and are happy to explain it to their perplexed parents: “A monkey and an ape are not the same,” / said Sage. “The monkey has a longer name.” In this book of funny, fanciful poems and woodcuts, Eric McHenry and Nicholas Garland pay tender tribute to parents and the children who run circles around them.

-

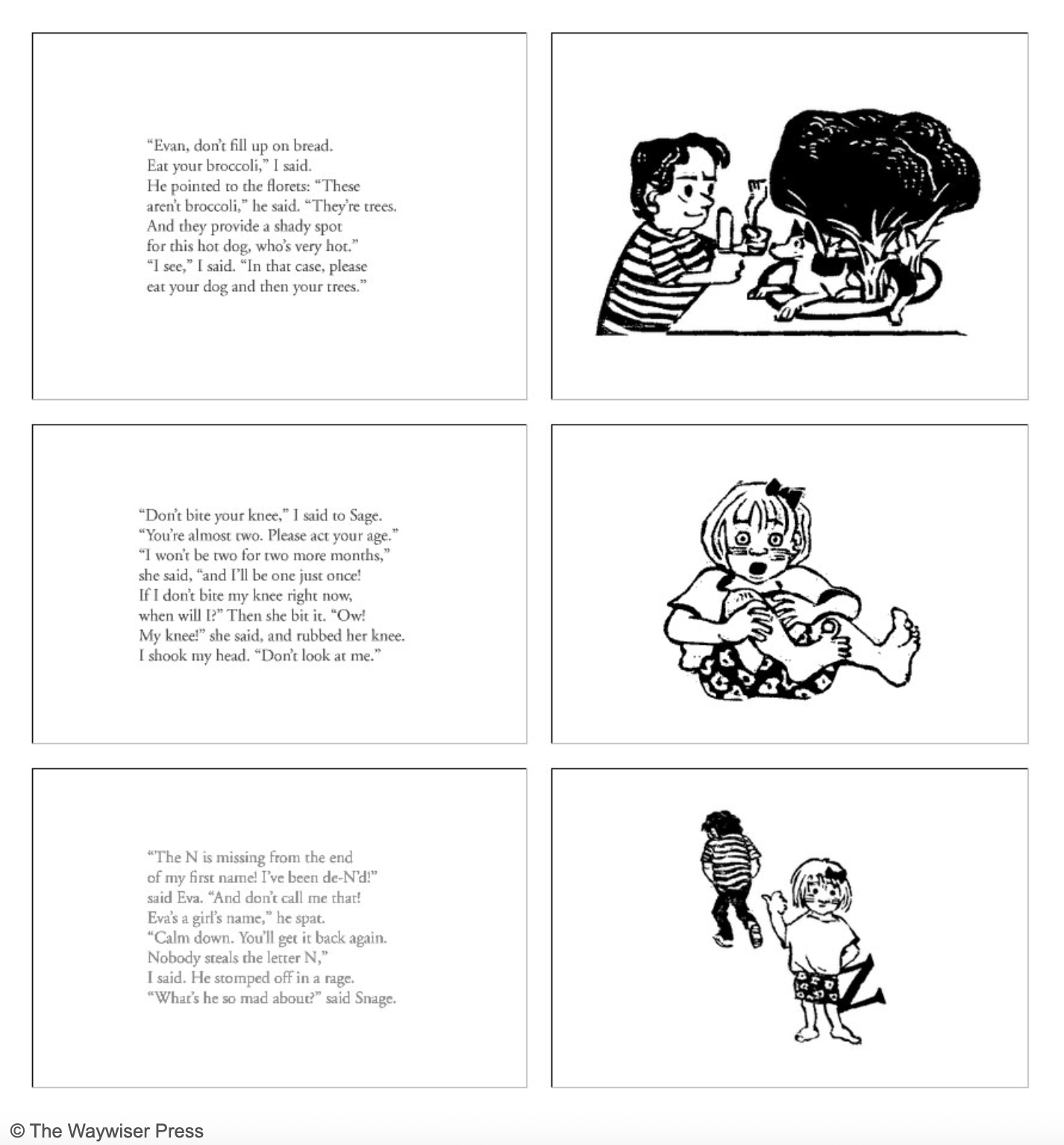

“A consequence,” Sage said, “is when/you take my favourite toy away/and I look at the floor and say/‘Sorry’ and get it back again.” This is one of the 30-odd poems in a delightful new collection from Eric McHenry, Mommy Daddy Evan Sage, illustrated with characteristic boldness by Nicholas Garland, and published by the Waywiser Press.

The poems celebrate quotidian family life, centring on two children – Evan, seven, and Sage, two – and the questions they ask, the theories they have and the unexpected flashes they show of knowing exactly how the world really works, as the above poem demonstrates. The girl’s coy glance out at the reader is a typical Garland flourish, and elsewhere his woodcuts complement the mood of the poetry beautifully.

The Waywiser Press, set up by Philip Hoy in 2002, is an independent publishing company that has brought out a series of quirky titles, handsomely produced and delightfully cheap." – Toby Clements

To read the whole of this review, please click: Full review of Mommy Daddy Evan Sage

Potscrubber Lullabies

by Eric McHenry

Pub: Jun. 22, 2006

Winner of the kate tufts discovery award

Potscrubber Lullabies aren't the kind that will put you to sleep. The poems in this first collection dance, dart, and double-cross, and are deadly serious the whole time. Preoccupied with impermanence and injustice, Eric McHenry wagers everything on the redemptive power of music, irony, and love. His language can be extraordinarily playful and self-aware – the double-negative "affirms / itself in no uncertain terms"; the census strains "the dead / from decade"; and a neighborhood blighted by Dutch Elm Disease learns that when "You take the elms from Elmhurst, you get hurt". But the poems always remain rooted in the sentence-rhythms of spoken English – in plain speech and "the plain fact of song."

-

"Every one of these poems is a little miracle of self-exactitude, rhyming and word play and metrical joy; they’re games the words in the poem play elatedly with each other, and everybody wins. The poems are victories of observation and self-observation, outsight and insight. I think there’s genius in this writing." – David Ferry

"This is a book that combines themes, places and music with wit and feeling, while letting them be what they are. Full of people, landscape and language treated with subdued newness. A great first book." – Aaron Fogel

"The exuberant, acrobatic poems of Potscrubber Lullabies are full of music and awareness of music. Along with their virtuosity, they have genuine feeling: generous laughter; a sneaky dignity free of self-importance; curiosity about the world; and an admirable sense of balance." – Robert Pinsky

"Eric McHenry’s Potscrubber Lullabies is a fabulous book, one of the best books I’ve read in years. Witty, poignant, offbeat, elegiac and satirical (sometimes all at once), with metrical subtlety and sly rhymes McHenry explores the idiom of place and the place of idiom. He reveals how even the most personal and intimate utterances lean ‘hard with the weight of someone else’s meaning.’ This debut collection marks the beginning of a new and significant voice in American poetry." – Alan Shapiro

"Potscrubber Lullabies is a funky, tough-minded, grown-up first book of poems, dangerously deadpan and winsome, as alert to large social realities like Midwestern floods and politics as to tiny motions of the soul. McHenry’s wordplay, a marriage of zany wit and truthfulness, never misses the beat or the point. Whether he is slinging his troubleball as John the Revelator, or declaring ominously, ‘When you say nothing I know what you mean,’ he has our number, and we have reason to be grateful." – Rosanna Warren

-

Virginia Quarterly Review, February 2007

“Ambrose Bierce drew national boundaries between humor and wit: ‘Nearly all Americans are humorous; if any are born witty, Heaven help them to emigrate.’ British publisher Waywiser Press accepts (for publication anyway) émigrés of the poor climate in this country for wit-wrought metrical poetry and they have preserved a rare specimen of American cleverness in selecting Potscrubber Lullabies …[This book] has many of the same elements as much more blah collections – strolled towns and graveyards, a kitchen window, a compost pile and wheelbarrow, a family, the eponymous Potscrubber dishwasher – but these poems do what many don’t: they are intent on and successful at leaving these scenes more memorable for the careful linguistic inspection. Normally suspicious when I hear the drumbeat of traditional forms, here I’m tempted to salute. Don’t let a few colorfully borrowed bars fool you: by the dawn’s early light, there’s something very American up at Ft. McHenry." – Kevin McFadden

Cranky, August 2006

“McHenry’s poems … range in content from familial issues to politics to pop culture to self-reflection. The themes are often familiar or funny, but always emotionally brightened by McHenry’s aural strategies: word-play, rhyme, meter and repetition. McHenry obviously delights in language … but his delight brings with it a serious outcome. Robert Frost claimed that poetry is ‘play for mortal stakes.’ Eric McHenry plays well, and touchingly." – Amy SchraderBostonia, Fall 2006

McHenry … muses serenely and often on “temporariness, the big unfairness”; left to nature’s whims, even grave sites and gravestones, the most permanent memorial most of us can hope for, shift (“I love this cemetery’s / asymmetries, although / it must be hell to mow”). Engaging observations are lit by straight-faced puns, off-rhymes, inventive metrics, and nonintuitive rhyme schemes, with their often-delayed jabs of humor.If you would like to hear Eric reading a poem from Potscrubber Lullabies ("The Incumbent"), click on the link below, which will take you to Slate magazine, where it is featured as poem of the week [for the week commencing June 20th 2006].

-

Potscrubber Lullabies

I

The Potscrubber completes a cycle

so vigorous the knives were rattling,

and pauses, waking Evan Michael,

who finds all silences unsettling.There’s no resemblance. It’s too early.

Everything is still so round.

But we’ve occurred to him as surely

as silence has occurred to sound,and when he’s finished sharpening

into himself, and when we’ve blurred,

we’re going to go on happening

in silence like he’s never heard.II

I wore him like a broken arm

all summer, slung

from my right shoulder in a paisley hammock

so deep the sides closed over him.

When I walked he swung, and slept,

lulled by the time his body kept

against my stomach.

When I stopped I had to sing.The Waywiser Press

Bird Plays to a Cow

A Swedish musician remembers a drive through farm country in a car full of musicians, one of whom told Bird that cows love music. Bird asked the driver to pull over ...” – Gary Giddins, Celebrating Bird: The Triumph of Charlie Parker

Fifty years from now

a writer, writing about me

playing to this cow,

will call the cow “he.”

There’s her udder, plain

as an udder, and yet . . .

something about what people want

a cow, or an audience, to be.Some painters haze the foreground

and render something in the middle-distance

unnaturally sharp, to remind the idiot looker

that this is a painting, not a pasture.The writer will probably do

something self-referential, too,

and will almost certainly call the cow “bewildered.”“Bewildered.” As though

I strode out here expecting her to nod

in time or stand on two hooves and applaud.

As though cows stand around waiting for something,

and not just anything, to come along.

Come on. What I do might confuse

you, but this cow was wildered when I got here.To this cow there is only the plain fact –

hot fence, sharp fence, shit,

puddle, tuft of grass, golden horn

in the hands of the brown man

who wasn’t here this morning and is here now,and notes, too –

after so much noise,

the plain fact of song.My friend,

the bewildered one who’s still in the car,

told me that cows dig music.

I choose to believe that. That’s what I’m doing here.

She chews. That’s what she’s doing here.The Waywiser Press